Editor's Note: This blog was originally published on May 26, 2017 and has been updated with information about other Deupree House and Cottages residents who have served in the Armed Forces. We thank you for your service!

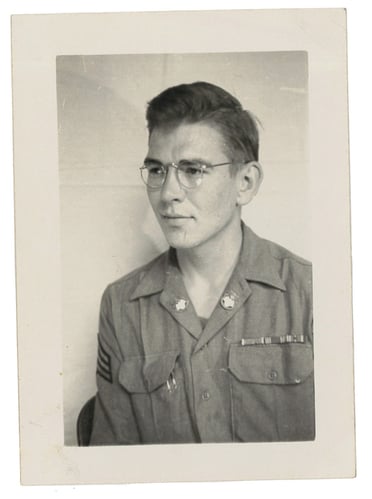

In his study at the Deupree House senior living community in Cincinnati, Bill Victor produces a copy of a Veteran’s Day speech he made at the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County in 1999 — the 55th anniversary of his Army division’s deployment to France.

“Most of you represent those who have made the same ‘down payment’ on freedom that we have,” he wrote. “Remember, it’s just a down payment. Our freedoms have to be paid for on the installment plan — they aren’t permanent and they aren’t free.”

"Our freedoms have to be paid for on the installment plan — they aren’t permanent and they aren’t free.”

Victor knows the price of freedom better than most. He survived the turmoil that so challenged Americans’ economic freedom throughout the 1930s. In the 1940s, he survived the fight to keep the world free from thuggish regimes that would attempt to subjugate it.

Many of his comrades didn’t survive that fight.

Learning to Deal with Disappointment

Victor grew up in East-Central Illinois—deep in corn country—the son of a man who lost a Ford dealership to the Depression, and the grandson of a country doctor few in town could afford to pay with cash.

Although farm families in the area kept the Victor family well-provisioned with fresh produce, sides of beef, sorghum molasses and other trade goods in exchange for his grandfather’s medical services, and although his father was lucky enough to score a new job working for a seed corn hybridization firm (an early form of genetic crop modification), they were still very poor.

Although farm families in the area kept the Victor family well-provisioned with fresh produce, sides of beef, sorghum molasses and other trade goods in exchange for his grandfather’s medical services, and although his father was lucky enough to score a new job working for a seed corn hybridization firm (an early form of genetic crop modification), they were still very poor.

Young Bill didn’t understand quite how poor they were until he asked his father one Saturday for a dime to attend the local movie house’s weekend Western serial.

“’Son, there isn’t a dime in the house for you to go to the movies,’” Victor recalled his father shaking his head and saying.

Shortly thereafter, young Bill ran out of notebook paper at school and, aware of his family’s poverty, asked his teacher for more. She told him that students had to provide their own supplies.

“We can’t buy it, because my dad doesn’t have a dime,” he recalled protesting.

In a small town like Tuscola, Victor said, “that kind of word got home before I did, that the Victors were too poor to buy paper for their kids.”

When he arrived back from school that afternoon, his father was waiting for him.

“I’m taking you to the store to get whatever you need for school,” he recalled his father saying. “We’ve always got a dime for school.”

Early on, Victor said, he learned to deal with adversity. To remain stoic. To, as the saying goes, keep calm and carry on.

“We had a lot of disappointments, just like anyone else,” Victor said. “It never seemed to linger with me.”

Enlisting in the Army

His ability to bear up under pressure carried him through hell on the Western European front. After graduating high school in 1942, at his father’s urging, he enrolled in college at the University of Cincinnati. He completed one semester.

Back home for Christmas that year, he contacted his local draft board and asked if he should send in his next semester’s tuition check. They told him it might be best to hang on to his school money.

So, Victor enlisted before his number was called and went into the Army’s advanced engineering program. He was assigned to the University of Oklahoma for nine months of basic engineering courses.

Returning to OU after furlough for another nine-month round of advanced engineering training—upon completion of which he would have held a collegiate degree and a 2nd lieutenant’s commission—he was told not to unpack his duffel. With D-Day looming, the Army needed more boots on the ground. His program was cancelled.

“They said, ‘You’re all in the infantry now,’” Victor chuckled, 74 years later. Then his face became more somber. That cancellation had been another great disappointment.

“My war would have been entirely different,” he said. One gets the sense that he was considering the many memories he would not have been forced to carry around these many years

Victor was instead shipped off to Camp Howze—still a buck private—for advanced infantry training. He was assigned to the 103rd (“Cactus”) Division as a 60mm mortar gunner which meant that, in the field, he was always “on the point” when his unit maneuvered. A mortar unit’s job was to probe until contact was made, then drop back, dig in and provide suppression fire.

Crowds gather around the lead tank of the 1st Battalion 400th Infantry task force, and 103rd Cactus Division, after soldiers entered without resistance in Innsbruck, Austria, on May 19, 1945. Jim Pringle/AP

Crowds gather around the lead tank of the 1st Battalion 400th Infantry task force, and 103rd Cactus Division, after soldiers entered without resistance in Innsbruck, Austria, on May 19, 1945. Jim Pringle/AP

While at Camp Howze, he met his platoon sergeant, Jack Scannell. The two would remain lifelong friends, until Scannell’s death earlier this year.

Several months later, they were on a troop ship, headed to Southern France in a convoy. The convoy was twice attacked by U-boats. Both times, his ship was spared—as much attributable to luck as to the excellent Navy escorts that sailed close along.

After landing in Marseilles and spending two more weeks assembling their Jeeps, halftracks, Sherman tanks and other equipment in a makeshift, warehouse district assembly line, the 103rd joined Patch’s 7th Army and moved to the front line.

Operation Nordwind

During the Nazis’ last major Western offensive, the bloody Battle of the Bulge, the 103rd covered the right flank for Patton’s 3rd Army, which pressed forward to relieve several encircled Allied divisions. His unit, L Company, was positioned across a 1,000-yard open field. On the other side was the German army.

“We could hear them bring their train up at night, with their food on it. Every once in awhile, we’d fire a mortar shell over there and, whenever we fired, they’d fire back, so we decided that wasn’t very productive,” Victor laughed.

But he doesn’t smile or laugh when he describes the action of January 19, 1945, when his division was sent to capture a small town, Sessenheim, on the French bank of the Rhein, just south of “the Bulge.” Intel had reported that the town was defended only by Volkssturm home guard units, comprised of old men and boys.

Unfortunately, the second part of the Nazis’ desperate offensive, Operation Nordwind (“North Wind”), had been placed in motion. The Volkssturm units had been replaced by crack troops of Hitler’s fanatical SS—armed with Tiger heavy tanks and 88 mm guns that easily penetrated the armor of the 103rd’s Shermans.

Approaching the town, L Company’s 8 supporting tanks were knocked out in the first 10 minutes of battle. The infantrymen were left “naked,” Victor said, and the situation became confused.

Victor’s platoon leader, already wounded, first ordered everyone ahead to take cover in a barn. Only half heard the command. After that lieutenant was shot and wounded a second time, he ordered the remainder to retreat to the cover of the woods.

One of Victor’s good buddies was among the first half who took the barn. Victor himself heard the second command and was chased all the way back to the woods, at a dead run, by mortar explosions and rifle fire. When he finally reached safety, he realized his squad mate wasn’t there.

The men who had gone forward to the barn, including his best friend, had all been captured—although Victor wouldn’t learn so until just before the German surrender, when his buddy was liberated from a POW camp and sent him a postcard.

Had Victor heard the first command, he would have been among them.

Just over 30 men were left from a company that had numbered 150 or so. The rest had been killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. That night—his mother and father’s dual birthday—Victor slept under a tank.

“Among my prayers that day was one that the Lord wouldn’t allow them to hurt me on their birthday,” he remembered.

During that engagement, Scannell earned a Silver Star by risking his life to drag the twice-wounded lieutenant to safety.

“Jack’s story is my story. We were together all the way,” Victor said.

After the armistice, “we realized that he, I and six other guys were the only ones still together from Camp Howze, Texas, to the end of the war,” he said. “And every one of us had a Purple Heart from being wounded somewhere along the way.”

Victor didn’t elaborate about his own wounds. Surely, the psychological wounds he suffered bothered him more. He talked about the first dead soldier he saw. He talked about the man in his unit who had a psychotic break after a dud artillery shell landed directly in his foxhole.

“They took him away,” he remembered, “and we never saw him again.”

He talked about liberating the Kaufering concentration camp—a feeder camp for Dachau, near Landsberg, Germany—at which the mostly Jewish prisoners were starved and forced to dig out large underground spaces where the Germans could secretly assemble fighter aircraft.

View of barracks after the liberation of Kaufering, a network of subsidiary camps of the Dachau concentration camp. Landsberg-Kaufering, Germany, April 29, 1945.

View of barracks after the liberation of Kaufering, a network of subsidiary camps of the Dachau concentration camp. Landsberg-Kaufering, Germany, April 29, 1945.

When his unit discovered the camp, Victor said, they found hundreds of dead bodies and hundreds more “living skeletons.”

“They were barely alive and some died as we watched,” he wrote in his 1999 Veteran’s Day speech. “We tried to reassure them, get medical attention and food for them, and keep them there to recover. They were so desperate to get home, to be free, they wouldn’t stay.”

But they were too weak to get far.

“For several days, as we continued our advance,” Victor wrote, “we saw their remains along the roads. The stench of that camp, and the evidence of man’s inhumanity to his fellow men, is a permanent, indelible memory.”

Adjusting to Life After the War

Following the war, he returned to UC, then attended the University of Illinois, and finally earned his engineering degree.

After college, he went to work for the phone company, but they didn’t have a job for a freshly-minted engineer. Another disappointment. They offered him a job as a splicer’s assistant — a role for which he was grossly overqualified and underpaid.

Victor took it. He was eager to learn the craft. Besides, he needed work. So, instead of turning it down and continuing to look for something that fit his degree, he made his education fit the role.

“That’s part of the Depression-era mentality. A job is the most important thing in the world,” he said. “My dad taught me that: your job and your wife.”

He grew that job into a 40-year career with Cincinnati Bell. He also married, had three children and now has seven grandchildren. His son, with whom he’d been speaking with on the phone just prior to our interview, is an editor for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

In late 1940s, when he feared the Cold War would soon go hot, he rejoined the Army as a member of the reserves, parlaying his degree and phone company experience into an officer’s commission in the Signal Corps. He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel over the course of a 25-year second military career.

Sharing Lessons Learned

Yes, Victor’s life has been full of disappointments. But it’s been full of triumphs, too. And he’s tried to impress upon younger people the lessons his Depression-era upbringing and service career imparted to him.

He’s given Veteran’s Day speeches at the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. He’s spoken to seventh grade history classes at local schools. And, he emphasized, he’s always been careful to depict the war exactly as it was.

“I try to convince them that nobody ‘wins’ a war. Everybody loses. And the guy that loses the least is proclaimed the ‘winner,’” Victor said. “War is not honorable.”

"No, freedom isn’t free. You must fight for it. And the fight for freedom is never over, he said, because someone will always try to take it from you and one has to “draw a line in the sand and defend it if necessary."

“Parades? Flashy swords and uniforms?” He shook his head. “It was dirty and cold and ugly. Every part of it. And I tried to convey that to the kids: don’t ever glamorize war.”

“It was the coldest, wettest I’ve ever been in my entire life. We had nothing dry,” he continued. “I swore then and there that neither me, nor my family, would be cold or hungry again.”

No, freedom isn’t free. You must fight for it. And the fight for freedom is never over, he said, because someone will always try to take it from you and one has to “draw a line in the sand and defend it if necessary.”

“I just wish I had enough voice to convince people that have never experienced war,” Victor said. “You don’t need to draw the line if diplomats do their job.”

“It disturbs everyone,” he said, “that senators and Congressmen, presidents and dictators decide who’s going to be at war, and then the million ordinary people have to go fight it. And that’s just all wrong.”

“We ought to put the leaders in the front ranks, like they used to be,” he laughed.

All those disappointments, and Bill Victor can still laugh. And he has a right to. Like so many veterans, he’s earned it.

This Memorial Day, we would like to thank all the veterans at Deupree House and Deupree Cottages, including Bill Victor, for their service. Click here to read more about our residents who have served in the Armed Forces.