Many Louisville and Kentucky seniors wonder, when considering a move into a retirement community or personal care community like Episcopal Church Home, whether they must divest their assets—homes, investment properties, annuities, vehicles and the like—to pay for their care.

Many Louisville and Kentucky seniors wonder, when considering a move into a retirement community or personal care community like Episcopal Church Home, whether they must divest their assets—homes, investment properties, annuities, vehicles and the like—to pay for their care.

Today, let’s look at the requirements and at some of the financial planning steps you can take to prepare for the care you and your spouse may need in retirement.

The simplest answer is that there is no simple answer.

The question of whether you need to divest an asset mostly depends on how you are planning to fund your retirement care. And, if your means of funding your care include Medicare or Medicaid, there are a few rules you’ll need to bear in mind.

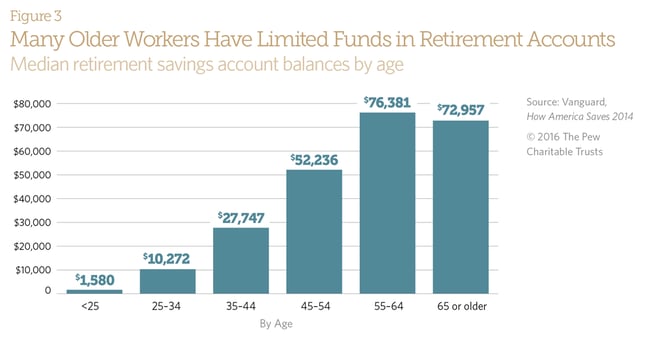

If your personal care will be funded via your savings in a 401(k), IRA or another private retirement asset, then you don't have to sell any of your property at all, unless you need to liquidate for unforeseen expenses, or unless those retirement savings run out.

You cannot usually gift or transfer title to adult and able-bodied children, other relatives, friends or to most trust funds without incurring an ineligibility penalty.

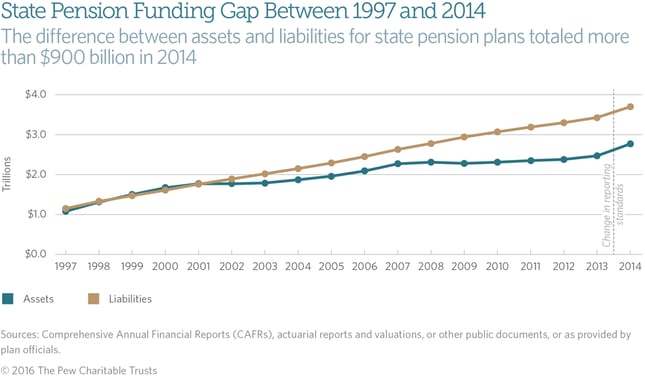

If Medicare or Medicaid benefits will be used to subsidize any part of your care, the state’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will attempt to recoup from your estate any expenses it paid for care on your behalf. In other words, before Medicare or Medicaid payments are made, you’ll be required to liquidate and spend down your disposable assets.

What are "disposable" assets?

In Kentucky, CMS considers anything other than the recipient's primary residence (for the first six months of your residency in a personal care care, or as long as your spouse and/or dependent child lives there; more on that below), a spouse’s primary personal vehicle, and certain cash limits to be subject to spend down.

This includes bonds, annuities, stocks, cash holdings and other investment valuables, vehicles, investment properties and second homes.

The state does not count IRAs, Keogh plans or other tax-deferred retirement plan funds against your Medicaid eligibility until you access them. Once you begin drawing income from them, that income counts against your eligibility.

The first $1,500 of a burial plot or life insurance policy’s value are not counted. Nor are personal effects and household goods. For more details about what Kentucky does and does not count toward your spend-down requirement, click here.

Can I transfer my assets to my spouse or to relatives?

Not generally. It can be tricky, if not downright illegal.

You cannot usually gift or transfer title to adult and able-bodied children, other relatives, friends or to most trust funds without incurring an ineligibility penalty (meaning you are not eligible to receive Medicare or Medicaid benefits for a certain amount of time—this is also known as being placed on "sanction").

Let’s say that you’re entering an personal care living arrangement, but your spouse is well and still living independently in your shared home. The house is protected if it’s your independent spouse's primary residence. Any jointly-held assets, however, are subject to spend-down, to the limit that the Commonwealth defines on your (the Medicaid recipient's) portion of ownership.

Say, for example, you own two homes: one is your primary residence in Louisville and the other is a vacation condo on the Gulf worth $300,000. The Louisville home would be protected as long as your independent spouse is living there. You would, however, have to sell the condo.

Before you do, though, it’d be best to consult with a lawyer who specializes in Kentucky's Medicaid eligibility regulations. You’ll want to make sure that you’re adhering to the letter of the law, but also managing your assets wisely.

What if a dependent other than my spouse is still living in my home when I enter personal care?

A Medicare or Medicaid recipient may, in most states, freely transfer title for a primary residence (not for disposable assets), without incurring an ineligibility penalty, to any of the following:

- A blind or permanently disabled (meaning the individual is receiving Social Security SSDI payments) child who is under 21 years old,

- A child of the recipient, who has lived in the house for at least two years prior the recipient's entry into a retirement home and who, during that two-year period, provided care that allowed the recipient to avoid a nursing home stay,

- A brother or sister who has (a) lived in the home for the entire year immediately preceding the Medicaid recipient's entry into personal care and (b) who holds an equity stake in the property

- Into a trust that has been established for the sole benefit of a disabled individual under the age of 65 (even if the trust is for the benefit of the Medicaid applicant, under certain circumstances).

Again, before you do anything, it’s highly advisable that you consult with an attorney who specializes in Kentucky’s Medicaid requirements as they pertain to estate planning and retirement care.

You can also request an asset assessment from the state, to find out what they will and will not look at. You, your spouse or someone representing you may ask Kentucky’s Department for Community Based Services (DCBS) to assess your combined countable resources.

You don’t have to apply for Medicaid to get a resource assessment. The assessment would compare your combined, countable resources to the state’s current Medicaid limits, to determine if you meet its resource guidelines. The assessment also sets the spousal share or the amount of resources your spouse may keep if you apply and are approved for Medicaid.

How do I figure out the best retirement plan to fit my needs?

The best course of action is to start planning early with help from a reputable legal expert and/or certified financial planner who specializes in Kentucky’s elder care laws and Medicaid regulations. Then, remember to be flexible enough in your planning to allow you to adjust as your circumstances dictate.

If you’re already thinking about your retirement care options for the near (or distant) future, now’s the time to start making decisions and to make your loved ones aware of your care wishes.

Ask your lawyer to draw up a living will. Remember to designate your medical and financial powers of attorney and set an advance directive. With the proper planning, you can make your transition to personal care as seamless as possible.