Linda Holthaus volunteers in development for ERS and is a docent at the Cincinnati Art Museum. She enjoys leading programs for caregivers and people with dementia. “It’s a real privilege to bring some joy into their life,” she said.

Sometimes when an armed police officer orders someone to do something, the person cannot – because they have Alzheimer’s disease or other form of dementia. Or they may have autism or be zoned out on illegal drugs.

Just because they’re not responding doesn’t mean they’re being disrespectful; training through a federal grant is teaching officers. A new program is training Cincinnati police to know how brain illnesses can affect someone’s ability to follow commands.

Not all brains work the same

About 50 officers in the past year underwent two-day training about dementia and autism, with others learning in smaller training throughout the year. The training is through a local program called GRASP, funded through a three-year, $150,000 Department of Justice grant.

During the training, Shannon Braun, director of Episcopal Retirement Services’ Center for Memory Support and Inclusion, and others taught the officers why brain conditions can prevent people from processing officers’ commands.

Alzheimer’s disease and the other family of disorders known as dementia create memory deficits. Among other problems they can cause for those living with them can be limited ability to communicate, with difficulty finding words. They can be anxious and confused, unable to follow directions, and even can experience hallucinations.

“Everybody deserves to be at the museum, but some people just need different accommodations.”

—Sara Birkofer, Cincinnati Art Museum assistant director of gallery and accessibility programs

A panel of families also told officers about their experiences – good and bad – with law enforcement.

One woman praised the help she received from officers when she couldn’t calm her husband, who was convinced people outside were coming to get him and about to break into the house.

“They checked everything out and said, ‘Sir, there’s nothing here, and we checked it all out, and everything’s good,’” Braun said. The woman said it was the only thing that calmed him down, and he went to bed.

She was grateful for their kindness and was embarrassed to waste their time on something that wasn’t a real emergency. But they made her feel better about it, saying, “That’s why we’re here; this is part of what we do. So don’t worry about it.”

They also were told about a man who had trouble answering when a Transportation Security Administration officer at an airport forced him to give his name that was on his driver’s license, but he couldn’t because of the stage of dementia he was in, said Debbie Serls, a social worker and the Cincinnati Police Department’s contracted GRASP advocate.

About 50 officers in the past year underwent two-day training about dementia and autism, with others learning in smaller training throughout the year.

Understanding dementia’s difficulties

Braun was pleased that the families on the panel who spoke with officers brought to life the scenarios she said could happen – even though they hadn’t heard her presentation.

Part of Braun’s purpose was to tell officers, “These are de-escalation techniques. These are good communication tips to employ with anyone you interact with,” she said. “You’re not going to know the person has Alzheimer’s all the time that you’re interacting with someone. You just have to try to figure it out, and if it happens to be substance abuse, or if it happens to be mental health, these tips should work for that, too, to some extent.”

ERS President and CEO Laura Lamb has set the goal of making Cincinnati one of the nation’s most dementia-inclusive cities in the coming years, and the Center for Memory Support and Inclusion is part of that.

Meanwhile, the police also have Serls as an important backup. Just as some people nationwide have called on police to hire social workers to help reduce deadly tragedies from conflicts with the general public, Serls can help when police are dealing with someone known to have a form of dementia or autism. She also can help connect their families with resources that can help them cope with other issues they are facing.

Museums also are helping

Meanwhile, several museums are working with Braun and other organizations to make themselves more accessible to people with various forms of dementia.

Braun has trained their docents about how the brain disorders can create problems for people living with dementia and how they can “go with the flow” in interacting with them, using the principles of “the 3Rs” and Improv techniques.

Many docents feel special joy interacting with these groups.

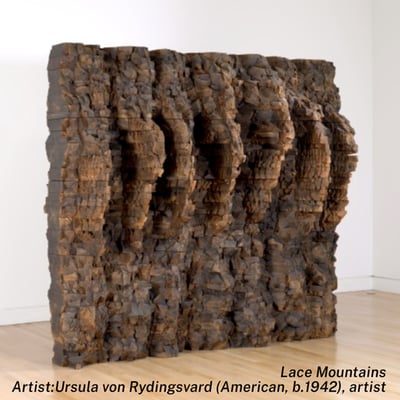

“Sometimes, you’ll get a surprise,” said Linda Holthaus, who volunteers in development for ERS and is a docent at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Once, while a group was viewing Ursula von Rydingsvard’s “Lace Mountains – a large carved-wood sculpture – a woman began singing, “The Bear Went Over the Mountain,” and most people joined in with her.

“It was just darling,” Holthaus said. “Or you’ll get comments like, ‘That lady’s looking at me. She thinks I’m handsome.’ It’s just very, very nice.”

“It’s a real privilege to bring some joy into their life,” she said.

Unlike other groups that visit, such as classes intent on learning specific facts about an art form, “It’s no longer about fact-finding, it’s smile-finding, and making them feel safe,” Holthaus said. “It’s a wonderful thing and has brought some of us docents closer together.”

Sara Birkofer, the Cincinnati Art Museum’s assistant director of gallery and accessibility programs, calls the dementia programs there “beloved because of the conversations that people are able to have and the good feeling that everyone leaves with.”

She adds: “No matter what your situation is, or where you are in either your journey with memory loss or with your journey as an educator here, you’re able to have really open-ended conversations.”

Docents embrace the improv style of interacting with the visitors; if the discussion “is going off in a different direction than we intended, we just go with it. And I think that creates a really positive experience for those people with memory loss who might be used to being corrected or being in the same space all the time.”

Instead of correcting someone living with dementia or autism and telling them that’s not right, the docents are more likely to roll with the flow with them. After all, art is supposed to be fun, Birkofer said.

In the museum, they’re also in a safe, beautiful space “where there’s so much to look at. And they can talk about whatever they want or whatever is coming to their mind. And that is why I think everyone really enjoys it. Because we’re getting to know each other, but also, it's improving the quality of life for these people with memory loss.”

Other programs are offered at the Contemporary Arts Center, Taft Museum of Art, and the American Sign Museum.

Caregivers and people living with dementia are part of a panel at the GRASP training so that officers can hear from those most impacted by the disease. In this photo from the most recent training, Shannon Braun, far right, poses with the group.

Helping families cope

One thing Serls does as the Cincinnati Police GRASP advocate is teaching police to treat families of dementia and autism with great empathy because when they have to call the police, they often are embarrassed – or fearful that Adult Protective Services will be called for dementia patients or Cincinnati Public Schools will be alerted for students with autism.

GRASP gets its name from the many-worded program name of Growing Community Engagement, Responder Training, Accelerated Response Time, Support for Families and Officers, and Program Sustainment.

A primary goal of Serls’ work is to help train families and first-responding emergency crews – especially police – that helps them during times of crisis, especially when someone with dementia or autism goes missing. A top focus of the program is to provide tracking devices that can help find the person with dementia or autism more quickly.

GRASP opens relationships between police and such families by making police agencies more transparent, Serls said.

“I think that if you look at history and police departments and even just news stories that you see, sometimes people become fearful of police, regardless of what their needs are,” Serls said.

Dementia communication tips:

learn how to reduce the frustration.

The program helps create protection for families, whether they use tracking devices or not.

“If you don’t, that’s fine, but you still have a resource within the police department that can get you resources, names, contacts, programs – whatever you may need,” Serls said. “And if you don’t have anyone else, reach out to us, and we will do 110 percent to help you.”

For the most part, the program is limited to people living within Cincinnati city limits, but Serls does provide people living in Greater Cincinnati lists of resources they can use for help.

She can be emailed at debbie.serls@cincinnati-oh.gov.

She also can be sent texts, with your name and home address, at 513-516-2582.

Serls describes her efforts as “just building a relationship so that people know that there are resources, but it’s not necessarily the traditional having to go to the police.”

“Having a social worker within the police department allows people to understand that there’s support there that doesn’t come with a badge and a gun,” she said.

As for the art museum, “Any training we can provide to our staff to welcome people with different abilities, that is going to help us be able to welcome them better,” Birkofer said. “What’s really important about that is developing that empathy and highlighting that everybody deserves to be at the museum, but some people just need different accommodations.”

Contact us today to learn more about how living at Marjorie P. Lee can help you or a loved one incorporate these “brain health” components into your own life.