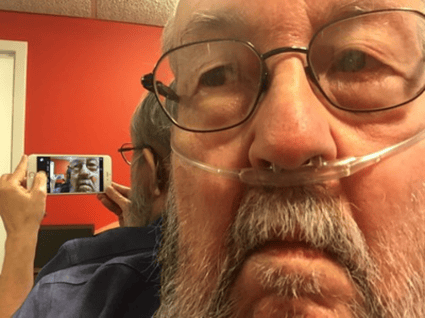

In his career as a cognitive psychologist and University of Cincinnati professor, Dan Wheeler was best known for his scientific brain. In his personal life, he's equally well-known for his artistic brain.

In his career as a cognitive psychologist and University of Cincinnati professor, Dan Wheeler was best known for his scientific brain. In his personal life, he's equally well-known for his artistic brain.

"I was a photographer first," he explained. "I was a very serious photographer in both high school and college."

As a teenager, he entered and won science competitions. He once won "a week in the Navy."

"We joked that second prize was two weeks," Wheeler said. "The Navy flew a bunch of us from all over the country to Boston, and we went out for a week on a heavy cruiser. They showed off all the stuff that they did."

At the same time, he was entering photography competitions organized by the Washington Star. He won awards and displayed work at the DC Department of Recreation's photographic salons.

He served on his high school student newspaper in Fairfax, Virginia, and, later, as chief photographer for the Yale Daily News.

"I considered going to graduate school for photography and design," Wheeler remembered.

In college, though, he was excited enough by new developments in psychology that he dove into the study of the field, leaving precious little time for conceptualization and darkroom work. As all of us do, Wheeler found himself at life's crossroads. And he chose first to follow a scientific path.

"I found in graduate school that being a serious photographer and being a doctoral student were not compatible."

He grinned.

But Wheeler's artistic impulses were always there, simmering underneath his work. Photography fed his soul, as it had his mother's before him.

Born creative

Wheeler's early life was spent in Heidelberg, Germany. His father worked for the U.S. Army in the 1950s, and the job required the family to live in Europe.

While there, his mother, Grayce, who had always been artistic in her own right, bought a Rolleiflex camera and became a serious amateur photographer. Dan and his sister were two of his mother's favorite early photographic subjects.

But there was more to it. At some point, Dan — then just a small boy — caught the shutterbug, too. He doesn't remember quite when, but his mother left him clues about his involvement in her work.

"I know I was taking pictures then," he said. "I recently found a tiny print that has written on the back that I took the picture. And it's a scene from the place that we lived in Heidelberg."

Clearly, the interest was there. And, upon the family's move back to Virginia in the latter half of the decade, he became his mother's photography assistant.

"Before we had a darkroom, she needed a totally dark space to load the film into the canisters for developing," he recalled. "It was my task to hold a blanket over the closet door to keep light from coming in around the cracks. And then pretty soon, I started taking pictures with her camera."

"That's how I got started," Wheeler said. "She mentored me through high school and encouraged me to compete with her in various contests."

Wheeler paid tribute to her influence in October 2014 when he organized a show of his late mother's work at Marjorie P. Lee, where he has been a resident since 2012. The show is archived here, on his website.

That's not the only show he's produced here. This month, in the third-floor event center, Wheeler organized an exhibition of work by members (including himself) of the Photography Club of Greater Cincinnati (PCGC).

Staying active through a creative life

Wheeler reclaimed his creative life 20 years ago while he was still teaching and researching at UC.

"I got involved in digital communications and working with kids and computers. Then, digital photography came along, and I said, 'Oh! I can do that!'" he recalled. "I could get back the control that I used to get in the darkroom."

At first, Wheeler scanned film negatives and printed them digitally. But he quickly moved over to a full-digital process. He bought his first digital camera in 1998 and learned how to use it, falling back on the photography basics he'd perfected in youth, which had stayed with him.

Although he’s had access to a full darkroom facility, he prefers digital photography. He finds it liberating.

"The computer's a lot more forgiving," Wheeler explained. "If you're manipulating with chemicals, you can't undo them. If you're dodging and burning, you can't see what you got until it's been in the developer and then you can't change it."

"With digital, I do a non-destructive workflow," he said. "I can undo everything I've done. If I don't like the way I've dodged and burned, I just erase that dodge and burn."

In his apartment at Episcopal Retirement Services' Marjorie P. Lee retirement community in Cincinnati's Hyde Park neighborhood, he maintains a digital production studio of sorts. He can process, manipulate and even print his work in his own home.

"I have a big computer set-up: two big screens and a Canon color printer," Wheeler said.

"I find [MPL] a very nice place to be." "I'm supported here in remaining active, doing things that I do of my own initiative."

In retirement, Wheeler has built his encore career as a serious, working artist.

His work has been mentioned in the New York Times. He's displayed in galleries, including the b. j. spoke gallery in Huntington, New York, and at Robin Imaging's semi-underground Mohawk Gallery here in Cincinnati.

"I'm really liking the shows Mohawk is putting on," Wheeler said. "I have a photo in the current show, Fire and Ice, that was taken here at Marjorie P. Lee. I called it 'Tongue of Fire.' It's a splash of copper color in a field of corroded copper."

Wheeler has entered — and several times won state awards in — LeadingAge Ohio's annual Art and Writing Show. He's developed a presence on Instagram and enjoys experimenting with smartphone-based photography.

And he's continued to concept new work. At present, he's working on entries for two shows and developing a new photographic study.

"I tend to think in series rather than individual images," he observed. "One of the things I'm working on now is a set called The Mis-measure of Women."

"It's photographs of women being measured in ways that don't make much sense," Wheeler explained. "There's one with a tape measure [positioned] as a blindfold. I'm challenging the notion of how women are measured and what ideal measurements are."

When shooting photos, he prefers to work alone.

"I go to a place where there are no words," Wheeler offered. "It's a heightened awareness of the visual."

"I haven't found it very useful to have other people with me, except when they're photographers, and they wander off on their own," he said, smiling. "I'm not sociable when I'm taking pictures."

Occasionally, though, on trips to visit his sister Emily in Oakland, California, he and Emily practiced the family craft together at towns and natural sites in the Bay Area. Now when Emily comes here, they go together to places like the town of Madison, Indiana, and the Pyramid Hill Sculpture Park in Hamilton, Ohio.

"That works out fine," Wheeler emphasized. "We don't want to be taking each other's photos, and we wander off and then get back together."

And, just as his artistic impulses stayed with him after he made his career choice to pursue science, Wheeler's instincts never to stop researching and learning haven't left him now.

"I think being an active senior means doing new things, continuing to learn, and continuing to be creative," he said.